By Anaclara Giurfa de Brito and Tarsila Iglecio.

With contributions Amelia Yates, Anna Magrì, and Sara Cano Diaz.

Edited by Jaqueline Aranduhá.

Leia este artigo em português em: https://uclcaos.files.wordpress.com/2022/05/violencia-territorial-e-o-corpo-indigena-feminino-2.pdf

The First March of Indigenous Women took place in Brasília in 2019. The march gathered approximately 2,500 women from 130 different Indigenous communities to demand the protection of their fundamental rights. The “Outcome Document” produced by the marchers stated:

“We are embedded in the land, since this is where we look for our ancestors and what we use to nourish our life. For these reasons, we don’t see our territory as a good to be sold, exchanged, or exploited. Our land is our own life, our body, our spirit”.

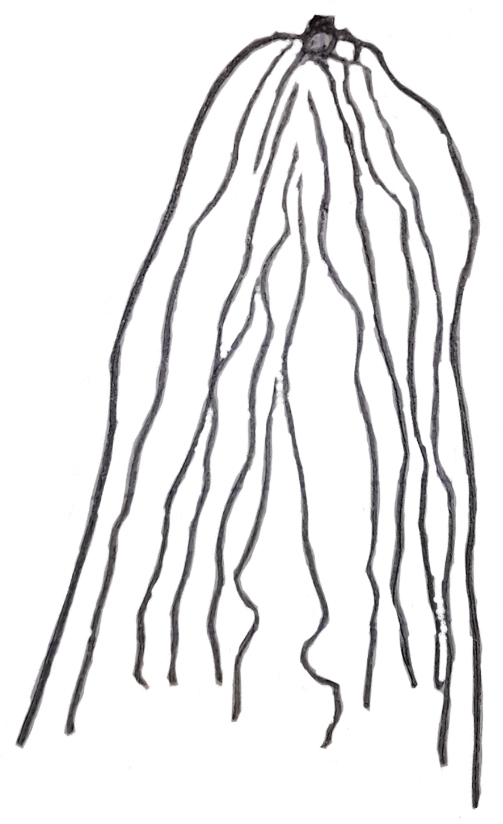

Across the world, Indigenous women have centred their resistance against violence by connecting land and gender-based violence. For Indigenous communities, the land is a core living aspect of culture. Indigeneity and womanhood embrace reciprocal relationships between territory, spirit, human and other beings (Kermoal and Altamirano-Jimenez 2016: 9). The struggle for equal access to the land is then not only a struggle for Indigenous sovereignty but also a struggle for the valuation of women’s bodies and reproductive work. The expropriation of territories involves simultaneously the transformation of women’s experiential meanings and life-forms into commodities. Going beyond notions of “property”, indigenous cosmovision of land embodies cycles, practices, and ancestral knowledge (Arvin et al. 2013: 21). Environmental changes can then endanger the community’s cosmology and survival.

The expression “cuerpo-territorio” (“body-territory”) emerges from Latin-American feminist, Indigenous, and afro-descendant movements and expresses historical violence perpetrated against feminized and/or racialized body-spaces. The Latin American communitarian feminists (feminismos comunitarios) have coined the concept of “cuerpo-territorio” by joining the fight for their traditional territories to the defense and protection of their bodies (Cabnal, 2015; CMCTF, 2017). The explicit union between the body and the territory introduces us to a particular way to move in the world – deeply rooted in an understanding of personhood, undistinguished from the land. “Cuerpo-Territorio’’ reveals a common and regional history of colonial and patriarchal relations of power where feminised bodies and territories are spaces for conquest and exploitation. The body is then a territory-place to conquer, with experiences, emotions, and sensations, while simultaneously becoming a space and tool of denunciation. In this way, land and bodies render oppression and humiliation visible through pain and memory. Their transformative relationship moves from spaces of conflict to resistance (Cabnal 2010; Cruz Hernández 2016; Segato 2016; Carrillo Rodríguez 2020).

Although “Cuerpo-Territorio” emerges in a Latin American context, its origins trace back to European cosmology, drawing dichotomies between culture/nature, male/female, and civilization/wilderness (Cronon 1996; Ulloa 2016). As nature previously contained places with little to no population, the European notion of wilderness expressed a fearful understanding of the natural environment, associated with the inability to control and exploit spaces. Likewise, womanhood was historically interrelated to nature which allowed European societies to present both as ‘territories of subjugation’. When these notions were brought into the colonies, the confrontation with the ‘other’ left colonisers with a vision of ‘chaos’, ‘uncontrollability’, and ‘uncivilisation’. New territories seemed to present a challenge for their domestication and exploitation explicitly leading to the legitimization of the use of violence towards new bodies and territories (Cronon 1996). In Latin America, this logic was institutionalised through the construction of nation-states, which legally and structurally allowed processes of dispossession and exploitation. Non-white and feminized bodies have been marginalized alongside undomesticated territories, targeted as spaces of conflict and violence. Their survival has thus proven the interrelationship to be strong and resilient, drawing a historical line of fight and resistance.

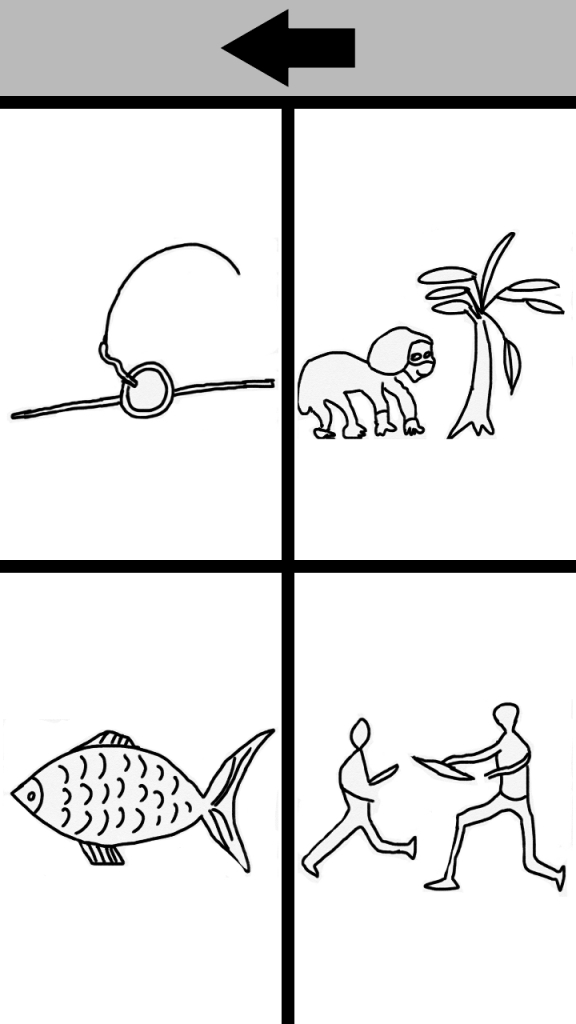

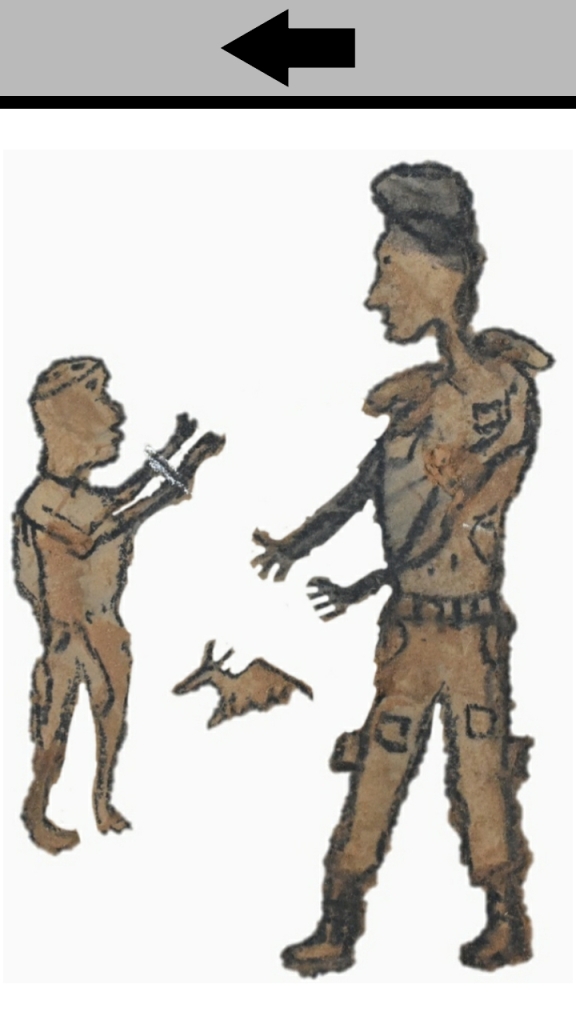

In Mato Grosso do Sul, Central-West of Brazil, the Great Assembly of Guarani and Kaiowá women – Kuñangue Aty Guasu – have undertaken the leadership of the community’s fight. Despite being the region with the highest incidence of violence, Mato Grosso do Sul is characterised as being one of the state’s “blind spots” for the lack of public policies and studies addressed towards gender-based violence. Additionally, the alarming violence Indigenous communities face every day is ignored and institutionally neglected (if not justified) leaving no political space for demands and equity. As a response to this, the Guarani and Kaiowá women decided to register and communicate themselves the violence the community is facing in their region. In 2019, Kuñangue Aty Guasu started collecting individual reports on violence through on-site visitations which led to the creation of a valuable database. This allowed them to write “Corpos Silenciados, Vozes Presentes” (“Silenced Bodies, Present Voices”), an insightful understanding of violence, bodies, and territories. In this work, they introduce us to the Guarani and Kaiowá cosmology and highlight the absence of the word “violence” in their native languages (Kuñangue Aty Guasu 2020). Despite this, violence seems to contagiously enter their communities, poison their lands, intoxicate their youth, reduce their territories, appropriate and silence their bodies.

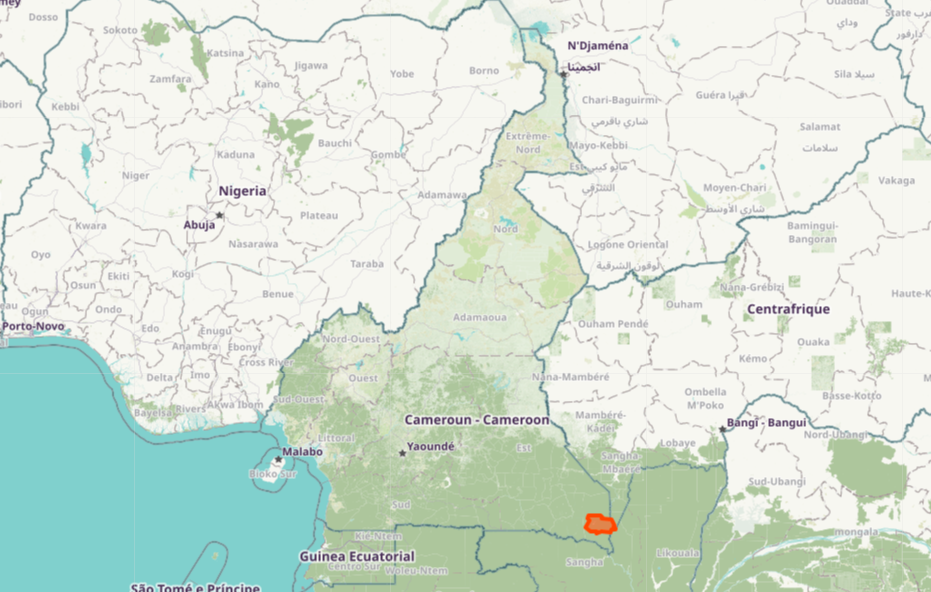

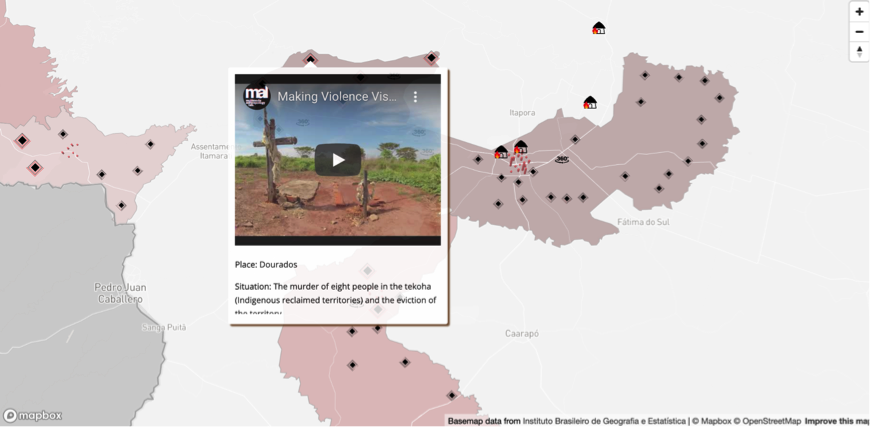

https://en.kunangue.com/mapainterativo

These 120 pages have then become the seeds to create an interactive map which would digitally amplify Guarani’s and Kaiowá’s voices at an international level. The creation of this map is the result of Kuñangue Aty Guasu’s work and resistance – supported by the ‘’Instituto de Arte e Cultura – IDAC” and the UCL Multimedia Anthropology Lab. The project was named “Making Violence Visible: Mapping Violence against Guarani and Kaiowá Women” and it initiated a multifaceted process of translation. The challenge was to ‘translate’ bodies and territories into digital voices of resistance. By adopting a “karai” (“non-Indigenous”) way to denounce violence, GK women showed how their fight needed to ‘bend’ and follow ‘dominant’ pathways in order to be heard and seen. Despite the pain and difficulty to quantify different accounts of violence, they identified and categorised 21 forms of violence. Several categories didn’t match with legal or internationally recognized violence, such as the “Brazilian state and the violence against our bodies” which intertwines genocide, epistemicide and ecocide. The map is a political tool, with audiovisual content that allows the viewer to feel and understand the emotional weight these territories carry, alongside the collective struggle and memory of GK women. Kuñangue Aty Guasu’s interactive map is thus the embodiment of survival, strength, and memory. It is constantly fed by new reports and incidents of violence, aiming to help its community to stand up against social injustice whilst also building a strong international network of solidarity and resistance.

Indigenous women are the most heavily impacted by colonial-patriarchal processes of land dispossession. The end goal has been the erasure of indigenous peoples and the possession of their territories; this is why women and their reproductive networks have been targeted (VLVB Report and Toolkit, 2016). Feminicidal violence is structured around the destruction of reproductive paths and ecosystems since it goes against the communities’ movements and practices on the grounds of ancestral land-based connections (Card 2003: 63). These ongoing assaults against Indigenous lands, bodies, and communal “webs of life” have made Indigenous women the protagonists of struggles against environmental degradation. In Mato Grosso do Sul, the collusion of power between the Brazilian state, local farmers, and transnational corporations is putting land defenders at extreme risk of violence. It is vital that the voices and experiences of GK women, and Indigenous women globally, continue to be heard and amplified, while their struggles against environmental degradation and climate collapse are strengthened.

Bibliography

Arvin, Maile, Eve Tuck, and Angie Morrill. 2013. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy.” Feminist Formations 25 (1): 8–34. https://doi.org/10.1353/ff.2013.0006.

Cabnal, Lorena. 2010. Feminismos diversos: el feminismo comunitario. ACSUR – Las Segovias.

Card, Claudia. 2003. “Genocide and Social Death.” Hypatia, 18(1): 63-79.

Carrillo Rodríguez, Eliana Carolina. 2020. “Cuerpos-Agua : Defensa y Cuidado Del Territorio a Través de La Experiencia de Las Mujeres de La Escuela Campesina de Chapacual, Nariño.” Undergraduate thesis. https://repository.javeriana.edu.co/handle/10554/49785.

Cronon, William. 1996. “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Environmental History 1 (1): 7. https://doi.org/10.2307/3985059.

Cruz Hernández, Delmy Tania. 2016. “Una Mirada Muy Otra a Los Territorios-Cuerpos Femeninos.” Solar: Revista de Filosofía Iberoamericana, June.

Kermoal, Nathalie, and Isabel Altamirano-Jiménez, eds. 2016. Living on the Land: Indigenous Women’s Understanding of Place. Athabasca University Press. https://doi.org/10.15215/aupress/9781771990417.01.

Kuñangue Aty Guasu. 2020. “Corpos Silenciados, Vozes Presentes: A Violência No Olhar Das Mulheres Kaiowá e Guarani,” November.

Segato, Rita. 2016. La Guerra Contra Las Mujeres. Traficantes de Sueños.

Ulloa, Astrid. 2016. “Feminismos Territoriales En América Latina: Defensas de La Vida Frente a Los Extractivismos.” Nómadas 45 (October).

Women’s Earth Alliance, and Native Youth Sexual Health Network. 2016. “Violence on the Land, Violence on Our Bodies. Building an Indigenous Response to Environmental Violence.” A partnership of Women’s Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network.